The 58ft Towing Lighters were the brainchild of Colonel John Cyril Porte of the Seaplane Experimental Station as a way to increase the range of the 'Felixstowe F2a Flying Boats and its variants.

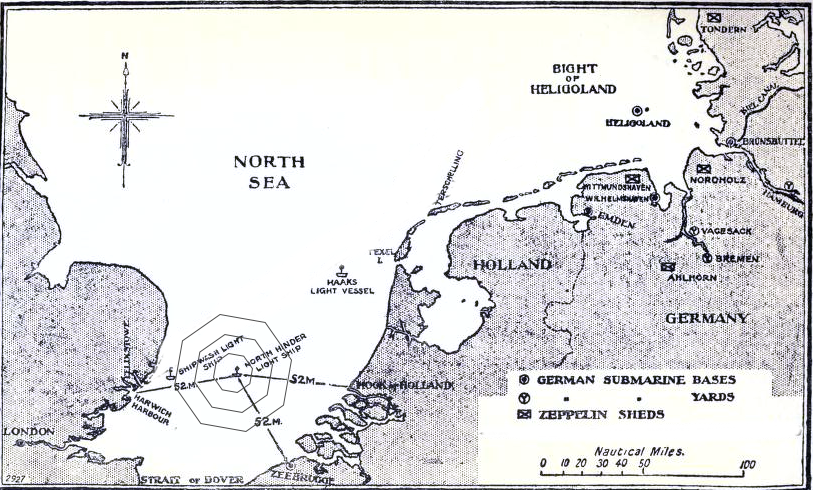

It was the job of the Felixstowe Flying Boats to patrol the southern part of the North Sea for submarines, mines and zeppelins in pattern known as the Spiders’ Web. However the German submarine pens and zeppelin sheds were in a heavily defended area of the North Sea called the Bight of Heligoland, completely under German control.

The Heligoland Bight was impenetrable to the Royal Navy’s surface ships but not to its flying boats such as those based at Felixstowe. However due to the large distances needed to be covered the planes lacked the range required to complete full reconnaissance missions into German territory.

Construction

Toward the end of 1916, Porte having already had great success in designing the Felixstowe F type flying boats, came up with the idea to create a flat-bottomed barge or lighter with a planing hull in which the flying boats could be towed at full speed across the North Sea, removing the need for the flying boats to traverse the North Sea under their own steam. The lighters were designed with flooding trimming tanks in the rear allowing the flying boat to be winched on and off at sea. Compressed air cylinders would then be used to pump out the water to refloat the lighter.

Once the destroyers arrived at their designated launching points the rear compartments of the lighters could be flooded allowing the flying boats to be launched, compressed air would be used to refloat the lighter for the return journey.Without having first to cross the North Sea, the F2as would have enough petrol to carry out long reconnaissance and return to England.

After much experimentation at the Admiralty Experimentation works a design for these vessels was settled on and orders for the first four vessels were placed by Thornycroft of Southampton with the first lighter being completed and tested in the Solent by June 1917. On the 3rd September, further trials were conducted in the North Sea leading to the order of 50 more lighters to be constructed at Richborough Shipyard in Kent, construction ceased after 31 lighters due to the signing of the Armistice.

Active Use

The first trip to enemy territory was on March 2nd 1918. Three F2as were secured to their lighters and towed across the channel to the Haaks Light Vessel off the Dutch coast. The F2a’s flew their mission, gathering intelligence on the Germans, before taking the 200-mile journey back to Felixstowe. The second lighter trip, 18 days later, confirmed the information gained from the first reconnaissance, allowing the Zeebrugge and Ostend raids to occur at the end of April 1918.

The lighters proved to be a great success, but during several subsequent lighter trips, the Zeppelin L53 was on station observing the flying boats, relaying their positions back to the Germans while staying well out of range of AA guns and the aircraft.

Lighters for Flying Camel Aircraft

Seeing how well the vessels towed, Rear Admiral Tyrwhitt and Colonel Samson came up with the idea of adding a flight deck to the lighter from which a fighter aircraft such as the Sopwith Camel could be launched under tow, to counter the German seaplanes and zeppelins.

By towing a lighter into the wind behind a destroyer at 30kts, sufficient windspeed could be built up under the wings of the aircraft to create lift, much like flying a kite.

Lighter H3 was loaned to Samson to begin his trials in May 1918 with himself as the test pilot. The first version took inspiration from the catapult launching decks used by ships like HMS Slinger. The flat deck featured runners in which a Camel fitted with skids would sit; when the lighter reached take off speed the Camel could then release itself from the lighter and theoretically get airborne almost instantly.

However, they did not consider the fact that when a boat planes,the bow rides up, meaning that the Camel had to take off uphill. This led to the aircraft stalling and falling off the port bow, destroying the aircraft, but luckily Samson survived.

Modifications were made to the flight deck to compensate for the raising of the bow, giving it a downwards sloping look when stationary. After much experimentation the new decked lighter was ready for another live trial at the end of July 1918, this time being piloted by Lt. Culley.

Culley’s trials with the new deck using a standard wheeled Camel proved to be a success with Culley getting airborne. Whilst on trials along the British coast the test pilots could fly back to land on shoreside runways. However in active use this would not be an option and the pilot would have to safely crash the aircraft as close to the towing flotilla as possible, where he could be picked up and the aircraft salvaged using a derrick fitted to the lighter.

Trials continued to perfect the lighter at sea until the end of the war.

Action of the 11 August 1918

On the 11 August 1918 a plan was formulated for the Harwich flotilla to take six Coastal Motor Boats out to the Bight to destroy minesweepers and other German surface vessels, accompanied by three F2as on their lighters and a fourth decked lighter towed by HMS Redoubt for Culley’s Camel. Three other F2as were set to join up with the fleet flying directly from Great Yarmouth.

The lighters were towed off the coast of Terschelling and the F2as were slipped onto the sea but due to long swells and a lack of wind they could not get airborne and were taken back on their lighters to be towed home. The CMBs supported by the F2as from Yarmouth continued their mission.

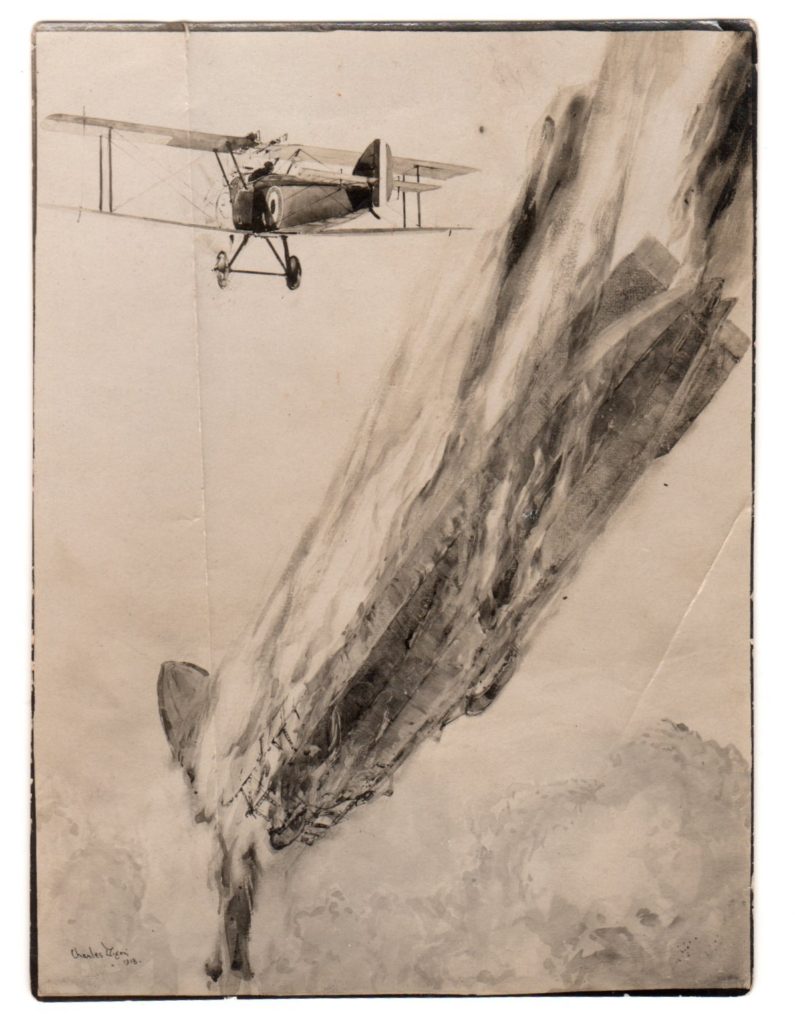

Once the Zeppelin L53 was sighted, Culley’s Camel was prepped for action and the Destroyer made its way up to 30kts into the wind. Running the engines full out, Culley managed to take off in under 5ft. At the same time the Yarmouth F2a’s spotted the Zeppelin and flew back to the flotilla to warn them, where they were ordered home. Once the F2as were out of sight the Germans deployed a squadron of monoplanes to attack the flotilla with little success but on their return journey to Bokrum they came across the CMBs. With no air support they were extremely vulnerable with half of the vessels being destroyed before escaping to the Dutch Coast.

During this action Zeppelin L53 was completely unaware of Culley who after almost an hour after take-off, finally came within range of the Zeppelin. Culley, at the extreme ceiling of his aircraft, pulled himself near vertical with his guns facing upwards firing both Lewis guns into the airship causing it to go down in flames, earning himself a DSO.

Culley then had to find his way back the flotilla. At 6000 ft and with only his emergency fuel supply left he could not see any British destroyers, so he decided to land near to a Dutch fishing vessel. However, on his descent he spotted the flotilla and was recovered to his lighter.

Aftermath

Not long after this event Vice Admiral Keyes commissioned Major Rutland, one of the most experienced pilots in the RNAS, to write a report on the best method of flying aircraft from ships. They both concluded that given the current technology the decked lighter was “undoubtedly” the best method and immediately ordered two decked lighters to be shipped to the Dover Command.

It was clear that the Germans still did not know about the capacity of launching fighters at sea given to the Navy by the lighters. Plans were concocted to repeat the actions of the 11 August, using the CMBs as bait to bring out the German planes and zeppelins from their bases where they would then be met by the Camels. However with the war coming to an end the need for flying boat patrols and attacks on German bases was diminished and the armistice was signed before any of the plans could come into fruition.

After the war the use of aircraft carriers were seen as paramount to the future of all navies as a way of projecting airpower over large distances. Specially designed flattop carriers capable of carrying multiple aircraft became the preferred method for launching at sea, with the lighters dropping off into obscurity.

Post War Use

The exact location and history of Lighters after the war is currently unknown. At least two continued their war service against the Bolsheviks in 1919, used to carry Fairey III seaplanes during the North Russia Intervention. It is likely that some lighters were shipped to other Seaplane bases around the UK, which had Felixstowe fleets, there is also some evidence the Royal Navy supported the Schneider Trophy participants with towing lighters or similar vessels.

Surviving Examples

There are three known lighters in the archaeological record

H21

H21 was operated by Thornycroft as a cargo barge on the River Thames from Platts-Eyott Island, Sunbury from 1932 to 1966. In 1996 her importance was realised, and she was brought to the attention of the Fleet Air Arm Museum, who, at great pain and expense recovered her from London and brought her to the Museum in Yeovilton, where she became the subject of a comprehensive restoration and research programme.

This is where BU began its involvement with Lighters, partnered with the museum curator Dave Morris, and a long-term collaboration project looking at the wreck of the lighter in the Hamble and comparing it to the FAA example began.

Hamble Lighter

This lighter survives as a hulk on the east bank of the River Hamble only a few miles from where the first four were constructed at Thorneycroft. Not much is known about this vessels history, although there is some circumstantial evidence that the vessel may be H3 the lighter used by Culley and Samson for their flights in 1918

The main hull survives on this lighter although the front deck has completely collapsed and it appears the deck plates have corroded away. The seaplane dock is filled with alluvium and general detritus, including a small wooden boat making it hard to create a detailed survey of the craft.

At some point during the vessels active life, the starboard bow cleats were replaced. Both bow cleats and a section of the stern have been recovered by the FAA museum to aid in the identification of the Hamble Lighter and the restoration of H21.

Poole Lighter

The Poole lighter is in the worst condition of all the known lighters. Although its presence was known about beforehand, it was only identified as a lighter the day after members of BU staff visited the lighter in the Hamble, immediately realising the identity of the Poole vessel.

The earliest record of the vessel on Brands Quay is a photograph from the Cyril Diver collection taken in 1935 which shows the vessel with a significant upper structure present, suggesting that it was converted from its original use to a houseboat. It is likely, given its current condition, that the stern was partially submerged at high tide, allowing the owner to slip a small boat. This image was compared to a collection of photographs of the Poole Harbour Houseboats by Andrew Hawkes of the Poole Maritime Trust revealing one likely candidate photographed in c.1927.

The next reliable photograph of the lighter is in 1952 which shows that the upper structure has been removed, as well as the decks between the 2th and 4th bulkheads (9th and 24th frame) but with the sides still intact and the stern submerged. By 1963 it appears that the side walls between the 2th and 4th bulkheads had collapsed leaving the stern section and the bow upstanding. The bow appears to have collapsed by 1966 and by 1977 the vessel was in much the same state as when the lighter was first recorded by BU in 2011.

The lighter currently sits in a bed of silt at the approximate level of the waterline, suggesting that everything below this point survives. The bow post protrudes approximately 200mm above the surface of the mud and a section of it lays disarticulated nearby. The outline of the water tight bulkheads, side walls and trimming tanks can only just be seen protruding from the mud. After the 5th bulkhead (30th frame) the framing takes up the whole hull of the vessel to support the slipping of the seaplane with a frame every foot, this is the section designed to be submerged and is what survives on the Poole lighter. The deck of this area has eroded leaving the structural details visible. The area forward of bulkhead 5 has collapsed over the winter of 2015.

The towing bridles also lie disarticulated on their respective sides of the wreck, with heavily corroded chain still intact